Caution: This project contains content, images, and design concepts that some readers may find disturbing. Please note that all of the work published here is speculative and not real. The persons shown in the images are hired actors, and the scenarios they are acting out are fictional. The purpose of the work is to investigate the possible role of design in the questions that surround assisted suicide and end-of-life scenarios.

Sincerely, Toward a Contemporary Design of Assisted Suicide

Natsuki Hayashi’s master's thesis, titled Sincerely, explores a contemporary design of assisted suicide. Utilizing design to reimagine the way we die, Natsuki pushes the boundaries of the legally, morally, and emotionally appropriate ways to end life.

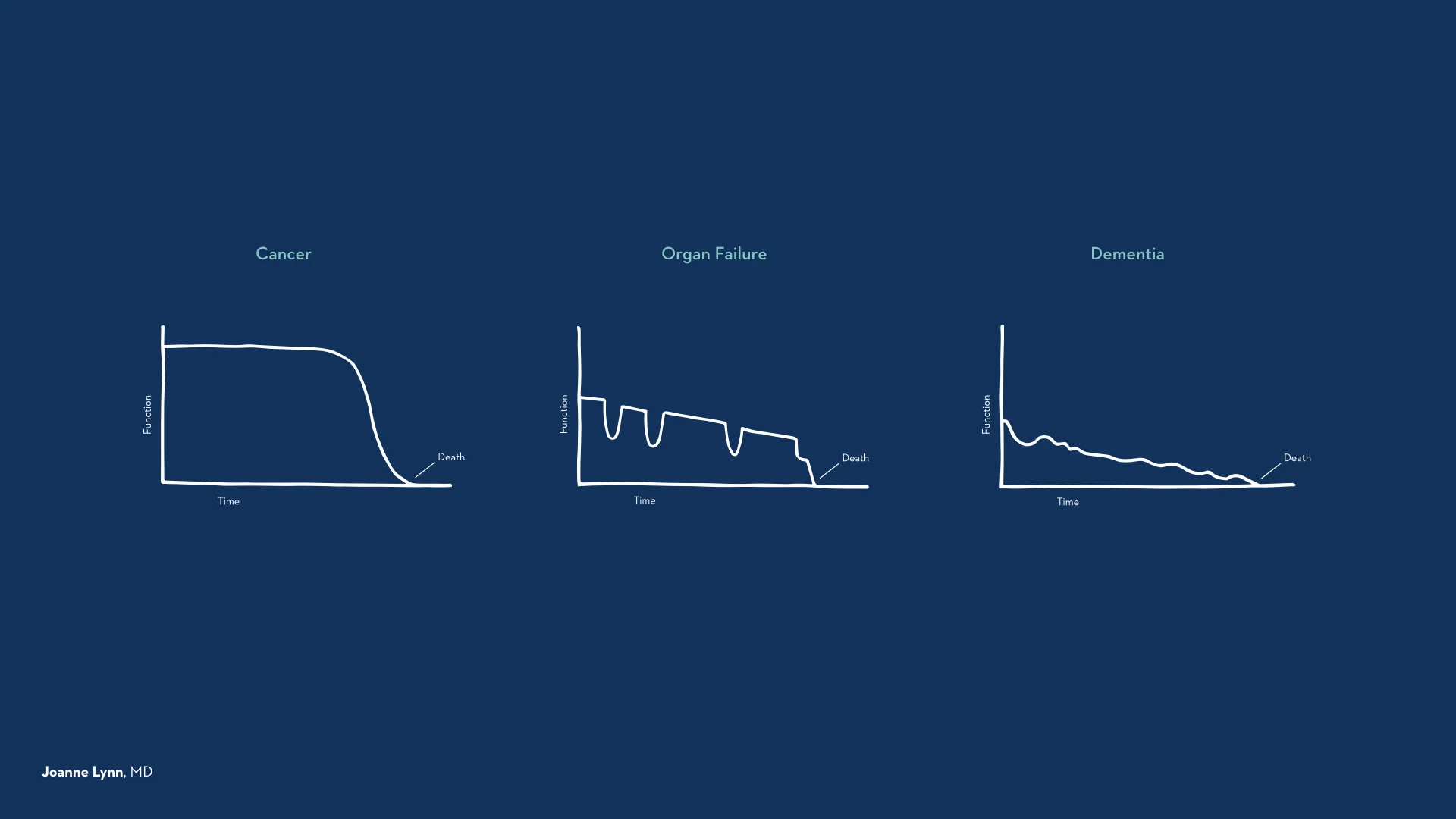

“We are living in a contemporary world of slow deaths,” writes bioethicist Margaret Battin. Indeed, deaths have specific shapes to them. But with deaths that are predictable, occur later in life, and can be delayed for longer periods of time using advanced medical technology, doctors can do a lot to prolong life—even if it means more suffering for the patients. Today, most doctors have no choice but to help end the lives and suffering of their patients.

“It was a difficult conversation to have with my mother. I didn’t want to hear her talking about dying, but she wanted me to know that she doesn’t want to have a lingering life dependent on other people and machines.”

Several years ago, a good friend of Natsuki’s mother died in a nursing home, alone. Suffering from Alzheimer’s and age-related health issues such as severe arthritis, she was bound to her bed most of the time. After taking Natsuki to visit the nursing home, Natsuki's mother said to her, "If I ever become like that, just kill me." Natsuki remembers, “It was a difficult conversation to have with my mother. I didn’t want to hear her talking about dying, but she wanted me to know that she doesn’t want to have a lingering life depending on other people and possibly machines.” Natsuki had known this woman since childhood, and seeing her suffering at the end of her life, Natsuki realized that the inevitability of death and the necessity of having options and any control over how we die would be a noble pursuit.

“Times are changing in the domain of assisted suicide, and it is time for us to get involved—to be ahead of this change.”

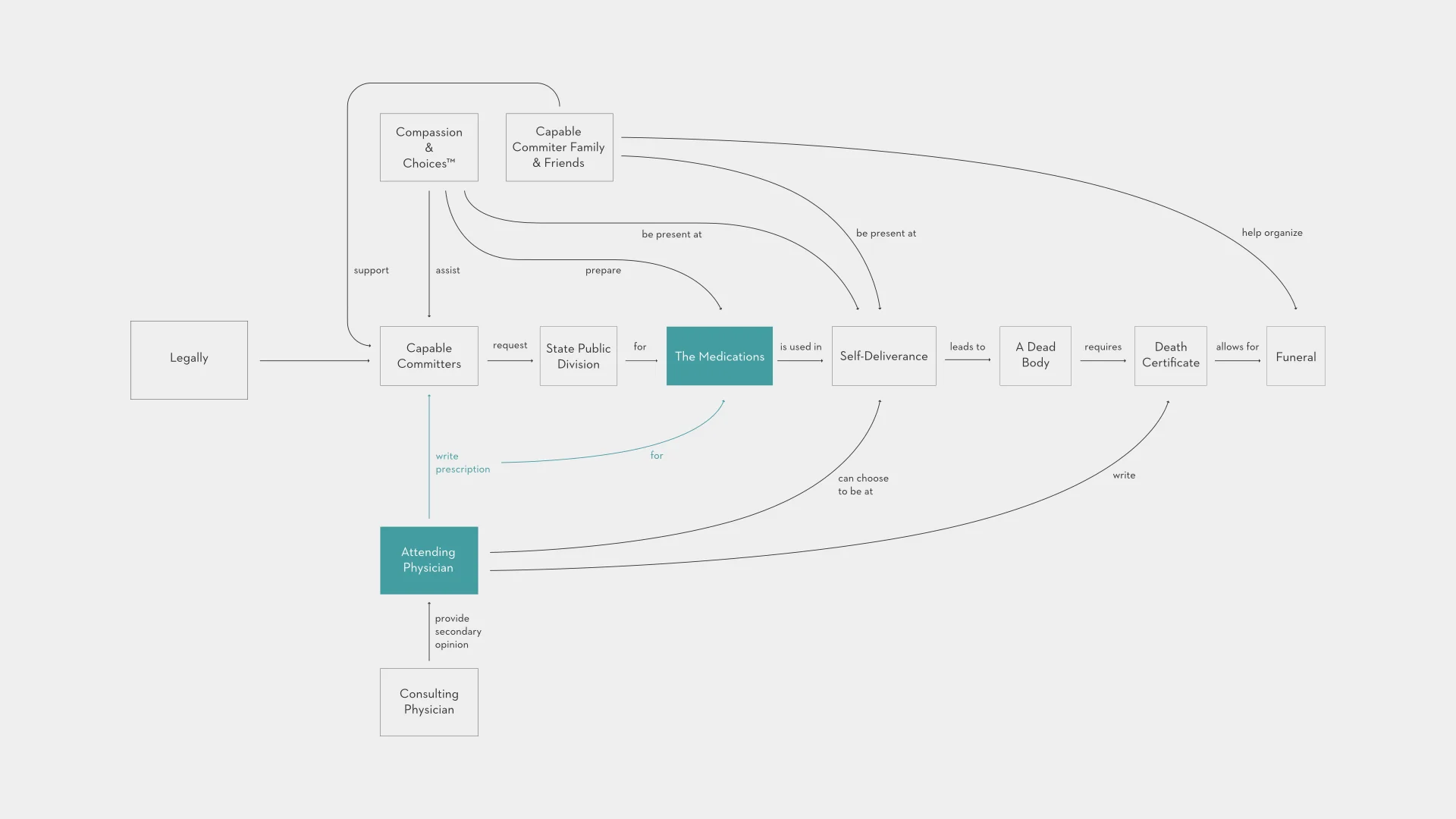

Death and dying—what were once a taboo subjects—have in recent years become an topics for serious discussion, and progressive attitudes and legislation toward assisted suicide is on the rise. Today, five states in the United States—Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont, and California—legally allow physicians to prescribe lethal medications, and more than twenty five states have aid-in-dying bills in their legislature. Natsuki argues that once we open up the conversation of how we want to die, we recognize that changing attitudes toward death and dying is creating a growing need for access to medically-justified suicide. She quotes Dr. Timothy Quill, Professor of Medicine, Psychiatry, and Medical Humanities at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry: “Whether or not this practice is legalized, seriously ill patients are asking us to talk about it; they’re asking us to consider it seriously.” Natsuki believes that "times are changing in the domain of assisted suicide, and that it is time for designers to get involved; to be ahead of this change."

In the United States, people can currently achieve peaceful and accelerated death in two ways—legally and illegally. In legal states, patients can request a lethal amount of prescription medicine—such as barbiturates—from their physicians for their final exit. The medication often comes as a bottle of 100 capsules, which the patient is instructed to break apart in order to derive 10 grams of powder, and then to mix the powder with 6 ounces of water to create what's known as a "final cocktail."

Passage

Passage is a "final cocktail" kit, consisting of a cup, mixing spoon, and tray for preparing one’s last drink. Inspired by the Asian tea ceremony and tea sets, Passage introduces the element of considered and deliberate ritual into the preparation of making one’s final beverage. The components are made of raw wood to reflect the taste of the specific medicine used for ending life—often secobarbital—which happens to taste like wood. The materiality of the wood highlights its temporality as a food vessel. The form of the tray dictates the placement of opened and unopened capsules, with cavities mimicking the two sides of the broken capsule, and the round-bottomed cup is designed to encourage the user to drink its contents in one shot. Below is a video depiction of how the ceremony may take place. [This scene was enacted by two professional actors, and is intended as an illustration only.]

Note: The products and scenarios shown in the video above are not real. They are speculative designs created as part of an academic Masters thesis project. The work is a prototype only, constructed to investigate the potential role of design in the context of end-of-life issues. The persons shown in the images are hired professional actors.

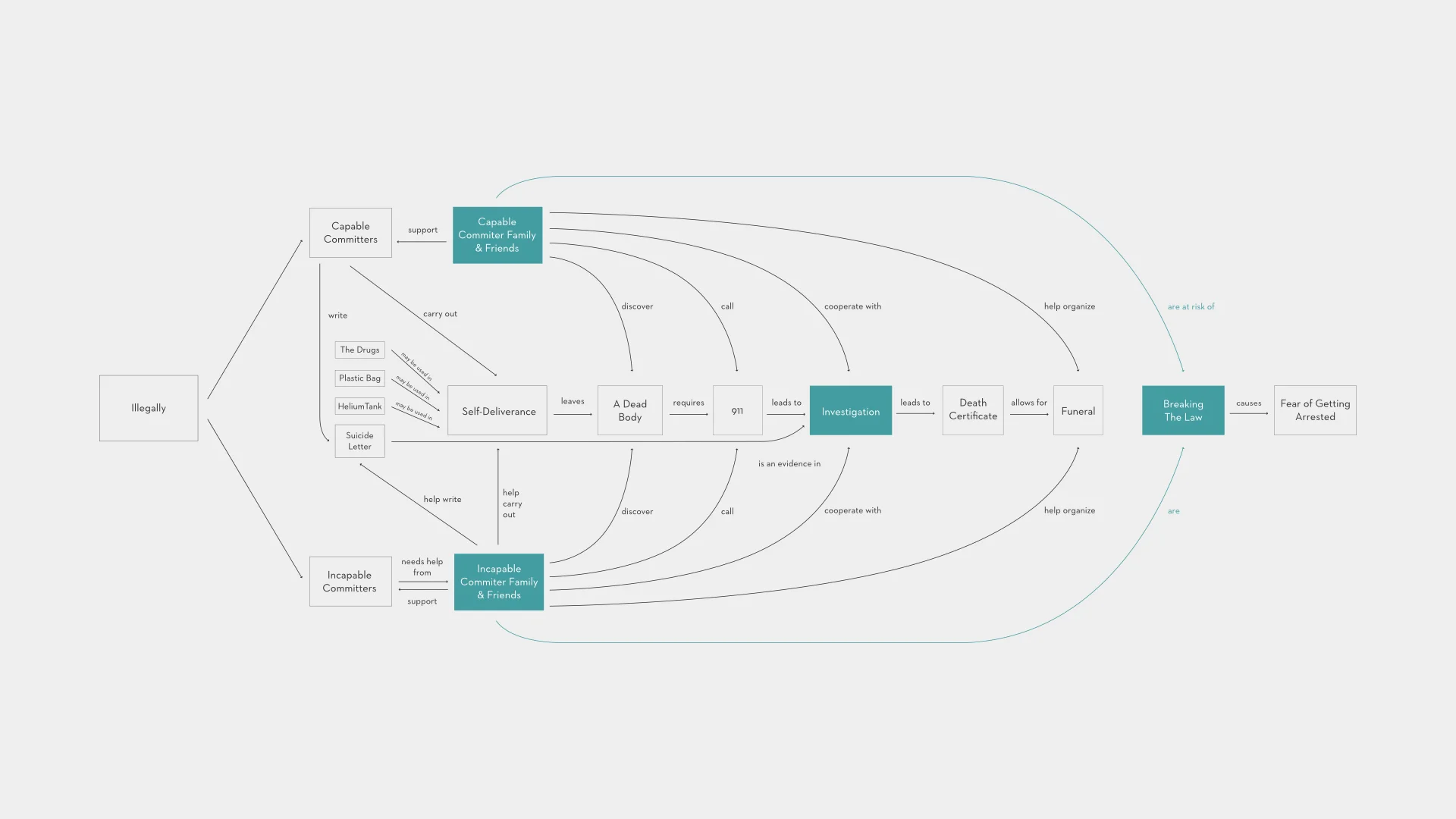

Where assisted suicide is illegal, every minute action must be carefully planned and coordinated with people they trust—to ensure that not only they can achieve a peaceful death, but also their friends and family are protected from getting arrested afterwards.

If patients have mental and/or physical difficulties ingesting medication—or live in states where physician-prescribed suicide is illegal—they may choose the route of peaceful suicide. And depending on their condition, they may need help or assistance from family members or friends. The process of planning and executing a medically-justified suicide, however, can resemble a theatrical production: Every minute action must be carefully planned and coordinated with people they trust—to ensure not only that they can achieve a peaceful death, but also that their friends and family are protected from getting arrested afterwards.

So for people who live in states where assisted suicide is illegal, but manage to obtain the appropriate medications, Natsuki realized that the Passage tray wouldn’t work: The wooden artifact would become a kind of evidence of the assisted suicide. So she decided to create a disposable version of Passage for people who live in states where assisted suicide is not yet legal. Constructed of paper pulp, the disposable version of Passage can be easily destroyed after the fact; when placed in a sink, it simply dissolves into the water.

Visor Hood

In lieu of prescribed medication, some people elect to take an overdose of sleeping pills, and to then cover their heads with a plastic bag. Visor Hood is a speculative product that attempts to ennoble the process of using a plastic bag. Once a person reaches a rational decision to end their life, but where no physician agrees to help, he or she can take sleep-aid medications and wear the visor hood. The visor creates a space between the face and the bag to remove the discomfort of the bag sticking to the mouth.

After placing the product into a real life context, Natsuki saw the disturbing imagery and the potential impact of this product—even though her intention was to help people who want to end their suffering.

"We shouldn't promote or romanticize the idea of double suicide, but perhaps we shouldn't condemn it either."

As Natsuki read more and more stories of people choosing to end their lives, she couldn’t help but think about the idea of "going together." The fear and the stress of the idea of being left behind, alone, can be so unthinkable, that some elderly couples choose to die together. (Her research revealed that in many cases, it almost doesn’t matter if both people are in poor health, or if only one of them is.) After learning more and conducting further expert interviews, Natsuki came to believe that if a couple feels they have lived full lives, and want to leave this world with their loved one, then they should have the choice to do so, together. She reasoned, "We shouldn't promote or romanticize the idea of double suicide, but perhaps we shouldn’t condemn it either."

On October 27, 2015, Peter and Pat Shaws ended their life together, both at the age of 87. They had a wonderful life together, and they couldn’t imagine life without each other. According to an article, The Big Sleep, their quality of life began to decrease as they aged and they chose to end their lives while they still had control over their life. Their three daughters were supportive of their decision.

Inspired by this story, and to respect the decision of a devoted couple reaching the end of their lives, Natsuki created a Couple Hood. The hood is inspired by Sharlotte Hydorn’s suicide hood, which uses helium. Breathing an inert gas like helium leads to loss of consciousness and eventually a peaceful death within fifteen minutes.

This method is said to be a fairly simple and painless way to die, since the body reflexively wants to breathe, but does not really care what it is breathing. When people breathe pure helium—or any other inert gas such as nitrogen—they don't actually feel any sensation of suffocation. They simply fall unconscious after a minute or so, and within fifteen minutes, are gone peacefully. With Couple Hood, two people put the hoods over their heads; one person turns a valve to release the gas from the tank, and the other person turns another valve, closing the system and trapping the gas inside of the hood. This design therefore requires the partnership and the participation of both parties to achieve their goal.

Without professional guidance, when something goes wrong during medically-justified suicide, people have nowhere to ask for help.

CompassionAid

People who don’t meet the legal criteria for assisted suicide can sometimes take matters into their own hands using the information and methods available to them. But sometimes death is not that quick and easy to achieve. Some people can take longer to die, and each person has a different tolerance to medications. So without professional guidance, when something goes wrong during medically-justified suicide, people have nowhere to ask for help. Under such circumstances, those who are assisting someone to die (often a trusted family member or friend) are under enormous pressure to help their loved ones. They cannot call 911, because they want to keep the police and paramedics away from the situation.

Here, Natsuki was shocked and inspired by a true story she heard from a man who helped his friend commit suicide. His friend was 75 years old and dying from throat cancer, and decided to end his life using liquid morphine. However, since he had a tracheotomy tube in his throat, he needed help from his friends. Tragically, after drinking an entire bottle of morphine, nothing happened. For some reason, the morphine wasn’t working, and everyone panicked. In the end, the suicide took five hours, a second bottle of morphine, and a plastic bag before achieving death.

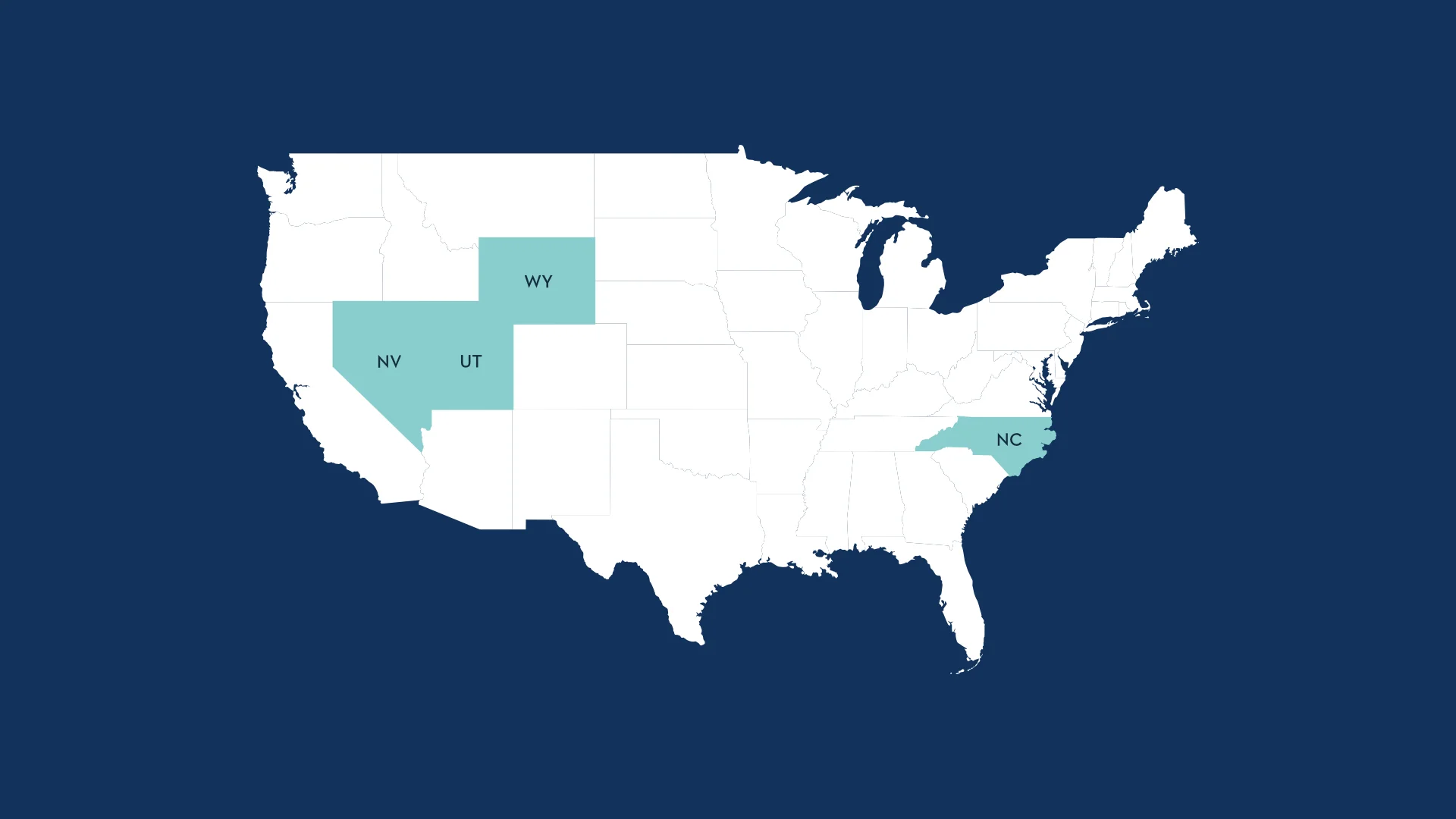

Here, Natsuki imagined a service called CompassionAid—a 24/7 hotline service that provides medically-justified suicide-related consultations. It is a safe place to reach out for support from trained professionals who can help reduce some of the stress and unknowns around suicide, and provide appropriate information and guidance. People call a toll-free number. That call is then rerouted to one of the four U.S. states where aiding and abetting suicide is not a crime. They are then connected to a trained professional for consultation and guidance. In this system, both the caller and the information provider are legally protected.

The service would be free of charge, because an offer of payment or other promise of compensation or reward is an element of solicitation, and can therefore be seen as a crime. Instead of charging for the service, CompassionAid incorporates a gifting model to sustain operations. After receiving the service, users can donate whatever amount they wish as a voluntary payment through the CompassionAid website.

"When a person has control over it, they can actually celebrate life—before it's too late."

The farewell party

Throughout Natsuki’s research and interviews, she was often reminded that death is not just about sadness. "When a person has control over it," she argued, "they can actually celebrate life—before it's too late."

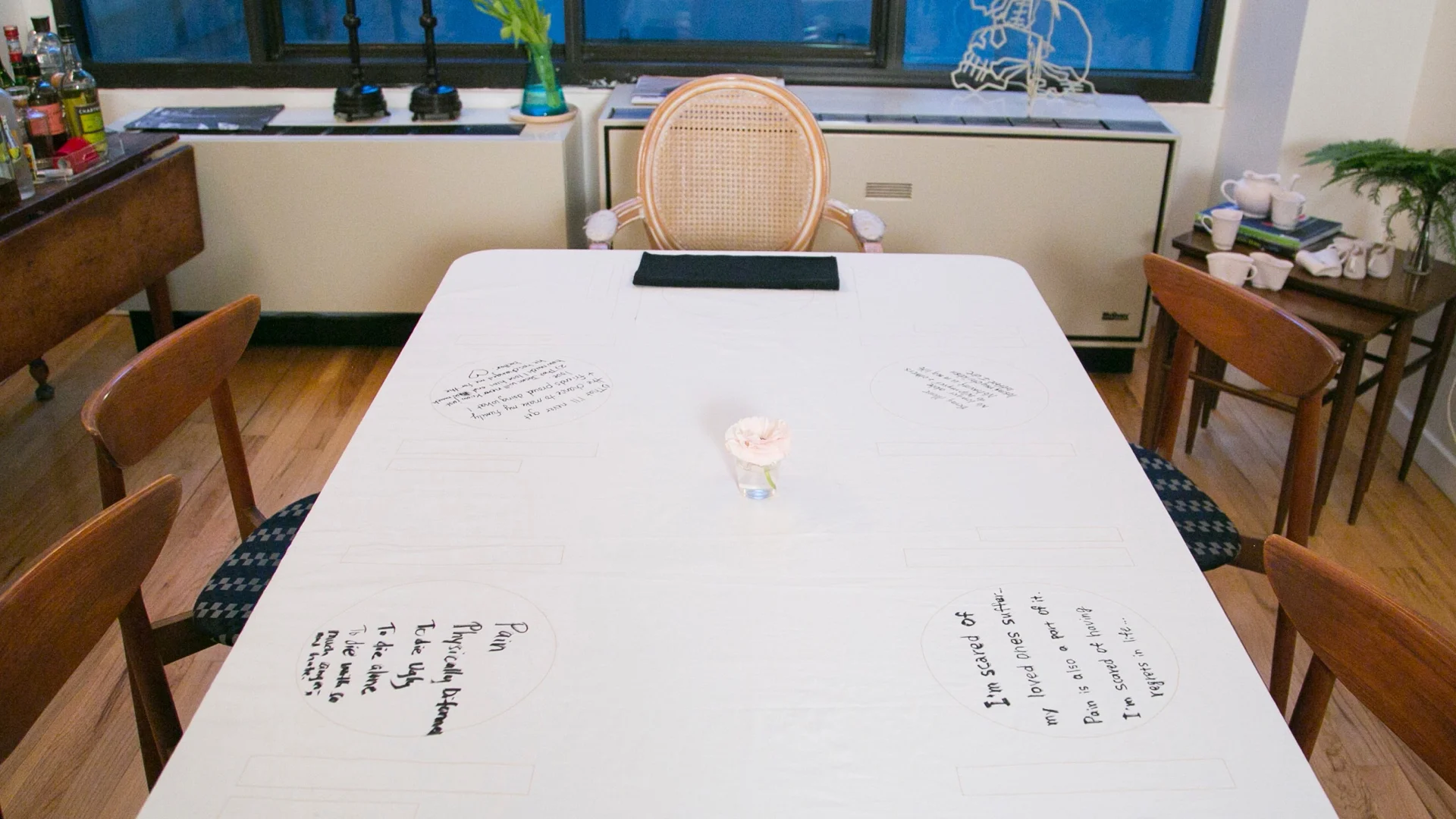

Inspired to create design work around this insight, Natsuki created and prototyped The farewell party—a dining experience that celebrated the life of Crysdian Llemson, a 46-year-old man who has been HIV-positive since he was 11 years old. The dying process is an intimate practice, so Natsuki wanted to create a personal experience where a group of people could come together to reframe the way they approach death. On March 20th, 2016, Crysdian and his close friends spent an intimate evening together around a dining table designed by Natsuki. The tablecloth brought the experience together, and served as a blank canvas for conversations about friendship, about life, and about death.

At the party, Natsuki served three of Crysdian’s favorite childhood meals. Throughout his entire life, whenever he was left sick or sad from medications, these were the comfort foods that would make him feel better.

Toward the end of the meal, guests were asked to use the fabric markers placed on the table alongside the silverware to write each of their biggest fears about death and dying, right onto the surface of the tablecloth. Natsuki's hope was that "by the end of the event, the guests would walk out the door without fear, knowing that Crysdian would have the tablecloth with him." She adds, "Originally, the event was for Crysdian to celebrate his own life, but in the end it became a reflection on the fears his friends may have had about death, and how they wanted to approach their own end-of-life. It turned out to be a shared experience."

2016